Lab 2 - Thinking Like a Computer

The purpose of this lab is to get you familiar with some of the most basic components of how computers operate: binary and logic gates.

This is a group lab with an individual grade. That means in class you will work together, but everyone needs to turn in a lab and you will all be evaluated and given the opportunity to revise on an individual basis.

Throughout the lab, you will see this symbol: ❓. This is a signal to stop, work on the question with your group, and write down the answer somewhere; on your whiteboard, on paper, whatever. The important thing is to save your answer. You will turn in your answers to these questions on Gradescope under Lab 2. You can submit images or files as the answers, so if you want, you can just take a picture of the answers.

For Proficiency credit, your answers should be clear (obvious what your final answer is) and correct.

For Mastery credit, your answers should show your work. That is, it should not just be an answer; you should have some written work showing intermediate steps you and/or your group mates took to get to the answer.

Part 1: Boolean and Logic Gates

True and False are called boolean values, or bools for short. Just like 7 is an integer, True is a bool.

From now on I’ll use 1 for True and 0 for False, as is the convention.

Logical Operators

You can perform operations on boolean values like 0 and 1 just like you can on integer values or on strings. However, just like you can’t multiply strings, you can’t just add booleans; in other words, True + False has no meaning.

Instead, there are logical operators that do have meaning.

and: Evaluates both sides of the operation and returns True if both are true.or: Evaluates both sides of the operation and returns True if either is true.not: Evaluates the operation and flips its value

Here are some examples:

True and True = True

True and False = False

True or False = True

False or False = False

not False = True

Combining Operations

You can combine logical operations together and evaluate them piece by piece. For example, take the following:

(0 and 1) or (1 and 1)

This will evaluate eventually to 1. (First to 0 or 1; parentheses first!)

You can write logical expressions without 0 or 1 in them, and then assign 0 or 1 to the variables you used in your logical expression.

(A or B) or (not (C and D))

You could then set A = 1, B = 1, C = 0, D = 1. Or perhaps A = 0, B = 0, C = 0, D = 0.

❓ Q1: In your groups, evaluate the following expression:

(A and B) and ((not C and D) or (E and F))

Where:

A, B, E, and F are 0

C and D are 1

Truth Tables

In mathematics, we can describe these operations using truth tables, like this one for and:

| x | y | x and y |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

❓ Q2: Write the truth tables for or and not. Then, write a new truth table that is different from both and and or by changing some of the values in the final column.

Logic Gates

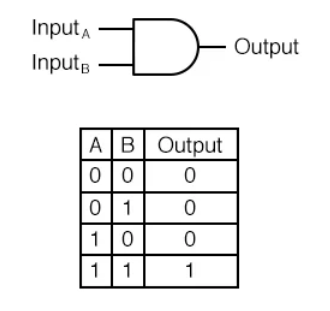

In programming, it is more common to see operations like and and or represented visually as gates. Here is what an “and gate” looks like, with its corresponding truth table:

Here we imagine the input coming into and leaving the gate through “wires”, and the gate decides what to output based on that truth table.

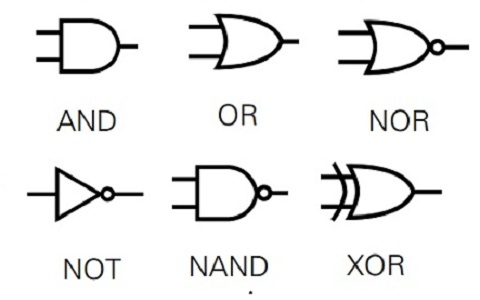

These gates are pretty standardized in their appearance.

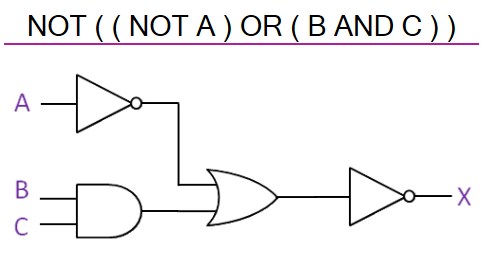

These gates can be chained together into logic circuits. Here’s a small example.

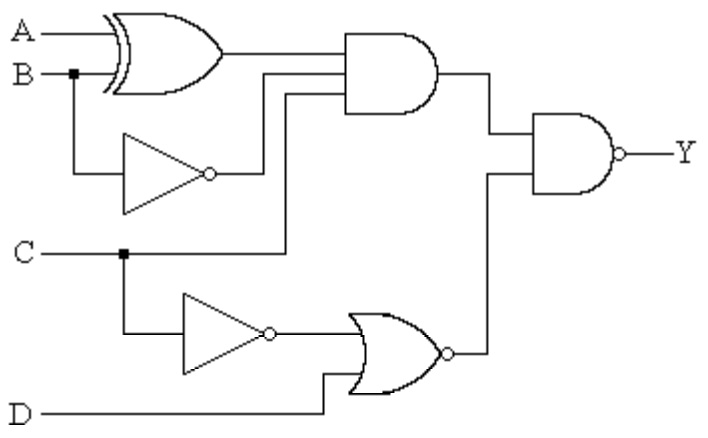

❓ Q3: In your groups, determine the output of the following logic gate circuit.

Part 2: Binary

You may be wondering why we use 0 for False and 1 for True.

The binary number system is a way of representing values that is different than how you may typically be used to representing numbers.

We represent numbers in base ten. That means that there are ten symbols to represent values, and beyond that, we need to use place values to represent values instead.

For example, we know that 9 means “nine”. And 45 does not mean “four five”; it means “forty-five”. It really represents (10 * 4) + (1 * 5).

Binary uses base two. That means that in binary, 1 means 1. But 10 means two: (2 * 1) + (1 * 0). And 11 represents three. To get four, we need to do 100: (4 * 1) + (2 * 0) + (1 * 0). These progressive place values are powers of two, just like tens, hundreds, and thousands are powers of ten.

❓ Q4: Figure out how to write the base-ten number 13 in binary.

How many bits?

Notice that 8 is just one more than 7, and in base 10 you just change the symbol you are using, but in binary it requires an additional place value. Much like 99 is just one away from 100, but you need a whole new place to represent the next number.

The number of bits (binary numbers) allocated for storage space is important, because in a computer, space is finite. There is no infinity inside a computer; there is only the biggest possible number.

Integers in Binary

So far we’ve looked at integers; these are represented within a computer with bits. There are 32 bits reserved for integers, but 1 of those bits is the negative sign.

❓ Q5: If there are 32 bits reserved for integers, with one bit reserved for negatives, what do you think the largest possible integer you can represent? You can check your work.

Note that negative integers are represented in what initially might seem like a strange way inside a computer. In Lab 5, we will return to this strange feature.

Bonus: Doubles in Binary

Doubles are also represented by bits. In fact, the word double refers to double-precision, as in it uses double the bits as floating-point values, which are 32 bits.

Like integers, their first bit is a sign bit. The next 11 bits then represent the exponent, and the final part represents the fraction. If this all seems confusing, it’s because it is.

The technical reasons for why this is a good system are beyond the scope of this class, but basically doubles are calculated like this:

\[(-1)^{S} \times 2^{E-1023} \times 1.F\]Where S is the sign (0 or 1), E is the exponent part (represented by the 11 bits), and F is the fractional part (represented by the remaining 52 bits)

I will not make you convert any numbers from binary to doubles. This is just to show you how they are represented.

This is the end of the lab. Make sure you have written your responses to Q1-Q5 and turn them in to Gradescope for credit.